Les Amis has some wonderful 300th Capital Project Campaign grant news! As most of you remember, early in 2020, Les Amis du Fort de Chartres asked permission from IDNR to begin a fundraising $100,000 capital project campaign in conjunction with the 300th anniversary of the building of the first wooden Fort de Chartres. We wanted to take the opportunity of this milestone anniversary to focus attention on the much-needed repairs at Fort de Chartres State Historic Site. We asked for permission to focus this capital project campaign for the repairs needed at the Fort’s Land Gate, the main entrance for visitors and a highly recognizable site feature. Les Amis du Fort de Chartres began our campaign and have made progress to our goal, a positive achievement considering the current economic environment due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Les Amis has some wonderful 300th Capital Project Campaign grant news! As most of you remember, early in 2020, Les Amis du Fort de Chartres asked permission from IDNR to begin a fundraising $100,000 capital project campaign in conjunction with the 300th anniversary of the building of the first wooden Fort de Chartres. We wanted to take the opportunity of this milestone anniversary to focus attention on the much-needed repairs at Fort de Chartres State Historic Site. We asked for permission to focus this capital project campaign for the repairs needed at the Fort’s Land Gate, the main entrance for visitors and a highly recognizable site feature. Les Amis du Fort de Chartres began our campaign and have made progress to our goal, a positive achievement considering the current economic environment due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

As part of our fundraising efforts, we were invited to apply for a French Heritage Society project grant, an American non-profit organization created in 1982 that includes 10 chapters in the US and one in France. Through various activities and their educational program, FHS is dedicated to preservation, restoration and promotion of the beautiful French heritage throughout the United States and France. Les Amis du Fort de Chartres requested and was given IDNR approval to apply for the FHS project grant and we were recently notified that we were awarded a $6,000 matching-funds grant to begin phase 1 of our capital project campaign. Our Fort de Chartres grant award is one of sixteen projects being funded by the Society, with the Chicago and Louisiana FHS Chapters specifically funding our award. We can’t express our gratitude enough for their support of Fort de Chartres. In their just published publication titled “Au Courant-Summer 2020” of the French Heritage Society, they announced their 2020 grantees which can be located at the link: “Au Courant-Summer 2020” or visit their website at https://frenchheritagesociety.org/projects/grants/

We are honored and proud to be included as one of their grant awardees (see page 16 of “Au Courant”). Even more impressive, we are 1 of only 3 awards given to a site in the United States-some pretty lofty company. But wait, the good news does not stop there! We were notified yesterday by the Society that they have received a matching grant award of an additional $6,000 from the William T. Kemper Foundation for our Fort de Chartres capital project, bringing the FHS grant award to $12,000.

With this grant award and the additional $13,430 in campaign funds raised thus far, Les Amis currently has gathered donations and pledges for our campaign totaling $25,430. These donations include an outstanding $10,000 campaign pledge from the Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Illinois and a $1000 donation from the Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Missouri. Please visit the donate page of this website for a full list of campaign donors. With more good news soon to be announced, we are confidently moving ahead in planning Phase 1 of the Capital Project focused on the Land Gate, under agreement and with approval of IDNR.

And a special THANK YOU, to all of the organizations and lovers of Fort de Chartres who continue to support the Fort and all of the history it represents. We really could not do this without your continued individual support. In the last 2 years of Fort event disappointments, do not lose heart. Great things are happening at Fort de Chartres. Stay tuned for updates. Merci à tous!

Please read the following article on the 300th Anniversary of Fort de Chartres and the related history from Dave Horne, long time Fort de Chartres supporter, reenactor, and past President of the Les Coureurs de Bois des Fort de Chartres..

Happy 300th Anniversary, Fort de Chartres!

By Dave Horne

The French wanted to develop their colony of New France, and in January of 1718 granted a trade monopoly to the Company of the West, which sold shares in the Mississippi Company to investors. In March 1718 the French frigate, “La Duchesse de Noailles” arrived at Dauphin Island, bringing officers and men to the Province of Louisiana. Onboard was Pierre Du Gue, Sieur de Boisbriand, lieutenant of the King and Knight of the Order of St. Louis. Now forty-three years of age Boisbriand was an outstanding officer of the French marine. In 1698 he had come to Biloxi, then as commandant to Mobile where he built the first fort in 1716. A year later he went to France and there received the most challenging assignment of his career, the commission of first commandant at the Illinois under the jurisdiction of the Company.

The convoy of bateaux that ascended the Mississippi to the Illinois Country carried three important persons: Pierre Duque, sieur de Boisbriand, appointed commandant of the Illinois Country; Marc-Antoine de La Loere des Ursins, a director of the Company; and Nicolas Chassin, storekeeper of the Company. These men along with a group of French Marines, skilled workmen and Company employees had three objectives, establish a military presence in the region, create a civil government, and provide a base of operations for the Company of the West. Their first task was to construct a fort to serve as a base for both civil and military operations.

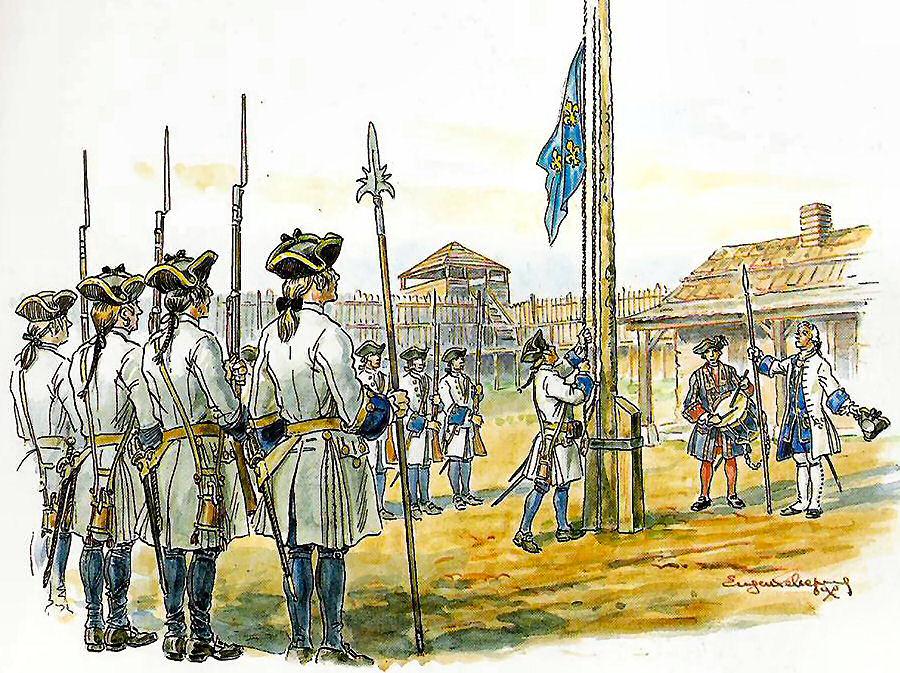

After months of preparations the convoy started up the river in October of 1718 and in December of that year reached the settlement of Kaskaskia founded in 1703. Boisbriand set up his headquarters in the village and housed his men and soon started his first task, to choose a site and erect a suitable fort to garrison his troops and provide a base of operations. He selected a site on the Mississippi River fifteen miles north of Kaskaskia, “a musket-shot from the river” and sometime in 1719 started construction. Built of wood it was completed in the spring of 1720 and the flag of France was raised above the new Fort. Boisbriand named it Fort de Chartres in honor of Louis, due de Chartres, son of the regent of France, Philippe d’Orleans.

The Fort was described just after completion, “Chartres is a fort of piles the size of one’s leg, square in shape, having two bastions, which command all of the curtains.” Within this structure resided a garrison of 60 marines, the Commandant, Company officials and a Jesuit Priest. By 1724 the village surrounding the fort consisted of 39 habitants (land-owning farmers), 42 white laborers, 28 married women, and 17 children. Jesuit missionary priests recorded the first baptisms in the village of Chartres in 1721 and this community soon developed into the parish of Ste. Anne, which survived until the British assumed command of the Illinois Country in 1765. So by the mid 1720s the Village of Chartres was a bustling center of the French colonial empire in North America.

During the eighteenth century, the Illinois Country, and so Fort de Chartres was important to the French colonial empire in North America for numerous reasons. Economically, the area produced furs, grain, and lead; geographically, it was the keystone of a vast arch of settlements and outposts running from the St. Lawrence Valley to the Gulf Coast; and politically, the Illinois Country established France’s claim to the heartland of North America and served as a determent to English advances west of the Allegheny Mountains.

While commandant of Fort de Chartres, Boisbriand conveyed land nearby to his nephew, Ste. Therese Langlois, who founded the town of Prairie du Rocher on the site. The town is one of the oldest French colonial communities to survive into the 21st Century in the American Midwest. Like several other French colonial commanders, Boisbriand was recalled to France in the 1720s to answer charges of mismanagement. He lost his military commission, but was later awarded a pension by the king. He died in France on June 7, 1736.

As with all wooden forts built in the damp area next to the Mississippi River, which eventually would be known as “The American Bottom” the first Fort de Chartres soon fell into disrepair and by 1725 needed to be rebuilt. French colonial soldiers often earned extra money by contracting to do specified tasks during their off-duty hours. In March 1725 troops from the garrison at Fort de Chartres contracted with the Company of the Indies to begin construction of the palisade wall for a new fort. According to newly discovered documentation the second Fort de Chartres was simply an enlargement of the first but with a double palisade wall and four bastions it was significantly stronger. The few extant source documents suggest that the second Fort de Chartres was built on the same site or was not far from the first. Though the deterioration process took longer, the second Fort de Chartres suffered much the same fate as the first one. Recent research has discovered that there was a third wooden fort built away from the river on higher ground. Archival and archaeological studies now indicate that the Laurens Site which for years was assumed to be the site of the first Fort de Chartres is in fact the third wood fort relocated due to constant flooding and built “on the prairie” in the early 1730s.

In 1731, the India company (successor to the Company of the West) retro ceded its patent and vast privileges in Louisiana to the king; and on April 10, 1732, by proclamation of Louis XV, the jurisdiction and control of the government and commerce of the country reverted directly to the Crown. Another government was at once organized for the Province of Louisiana, which separated it from Canada, but retained Illinois as a dependency. The third wooden Fort de Chartres was used for over 20 years prior to completion of the stone fortification in the mid 1750s.

In the summer of 1751 the Chevalier do McCarty, an Irishman by descent and a major of engineers was appointed Commandant of Illinois and Fort de Chartres. It was under his supervision that the fourth and final Fort Chartres was built according to plans and specifications drawn by Lieutenant Jean B. Saussier a French engineer. At this period the fort was the scene of much bustle and activity, and these were truly its glory days. In one of his Letters of Travel Through Louisiana, dated “At the Illinois, the 15th of May, 1753,” Captain Bossu of the French marines, in referring to the fort, says: “The Sieur Saussier, an engineer, has made a plan for constructing a new fort here according to the intention of the court. It shall bear the same name as the old one, which is called Fort de Chartres.” From this letter it seems that the actual building of the new fort was not then commenced, though preparations had no doubt been made for the work.

By now the French understood the importance of the area as a agricultural and trade depot. Fort de Chartres also commanded the all important Mississippi River, critical to transport and communication between France’s northern and southern colonies. Also with hostilities between long time adversaries France and England beginning to heat up once again the French wanted something impressive and substantial to act as a deterrent to British expansion and to keep their Native allies in awe of their military strength.

The government decided to rebuild a fort of stone near the first forts. There had been some disagreement about where to build the new fort but it was finally decided to build it where it now is reconstructed rather than at the other sites that had been considered. Construction began in 1753 and was mostly completed in 1756 however construction continued at the site for another four years. The stone for construction was quarried in bluffs about two or three miles distant and had to be ferried across a small lake that has long since been drained and turned into farmland. The limestone fort had walls 15ft high and 3ft thick, enclosing an area of 4 acres. Inside the walls stone buildings were constructed to serve as barracks for the soldiers, the Commandants house, a Government house used for government and civil business, a building used as a storehouse for commercial goods, a building with a guards room, officers quarters, gunners room, a chapel and housing for the priest. In one bastion was a bake house, in another a pigeon house and prison. The prison was under the pigeon house which must have been somewhat of a deterrent to crime. In another bastion stood the powder magazine which was the only building to withstand the ravages of time and the elements and remains standing on its original foundation. As with all huge construction projects there were modifications mostly because His Most Christian Majesty was concerned with the extravagant cost of the Fort. At one point it was even being considered to stop the project completely but the engineers and officers onsite convinced the Crown officials the construction was so far advanced it would be cheaper to finish it than abandon it.

The Seven Years’ War with Great Britain was now being vigorously waged and the demands upon Fort Chartres for men and material aid were frequent and pressing. Commandant McCarty labored steadily to meet these demands and several expeditions were sent out from the fort to take part in the great struggle. About the close of the year 1760, the veteran McCarty, after nine years of laborious service at this post, retired from the command and was succeeded by Captain Neyon de Villiers, a brother of Jumonville de Villiers who was killed in May, 1754, in the skirmish at Little Meadows, Pa., with a company of Virginia militia led by Lieutenant Colonel George Washington.

During the incumbency of Neyon de Villiers on Nov. 3, 1763, there arrived at Fort Chartres, in a store-boat heavily laden with goods, Pierre Laclede Liguest of the firm of Maxent, Laclede & Co., merchants of Now Orleans who, in 1762, had obtained from Governor de Kerlerec a special license to trade with the Indians on the Missouri river. After spending most of the winter at the fort, Laclede proceeded up the river in February, 1764, and established a trading post which would eventually become the present city of St. Louis.

In 1763 the French and Indian War (The Seven Years War) officially ended in France’s defeat. The Treaty of Paris ceded all land east of the Mississippi to the English. The British tried several times to move troops to occupy their newly acquired Fort but largely through the resistance of the French allied Natives they were unsuccessful. Finally, in the first week of October, 1765, Captain Thomas Stirling, under the orders of General Gage, arrived from Fort Pitt, with 100 Highlanders of the Forty-second British regiment, to receive possession of Fort Chartres. And on the 10th of that month Commandant St. Ange formally surrendered the post in a lengthy document, describing in detail the fort, its buildings, appointments and guns. Then the white banner of old France, with its royal fleur de lis, was drawn down from its staff, and in its place was displayed the red cross of St. George. Thus was ended the dream of French conquest and dominion in North America. After the performance of this sad act, St. Ange the last French Commandant took his departure by boat, with his small company of 30 officers and men, and proceeded up and across the Mississippi river to the new French trading post of St. Louis, which was then in Spanish territory.

During the year 1766 Captain Philip Pittman, of the Royal British engineers, reached Fort Chartres in pursuance of his orders to examine the European posts and settlements in the Mississippi valley. In his official report he describes the fort and its buildings and made this observation, “It is generally allowed that this is the most commodious and best built fort in North America.” He also reported that at the time of his visit the current had eroded the river bank until it was only 80 paces from the fort, a situation that would get increasingly worse.

There was a succession of different British Commandants and regiments stationed at fort de Chartres but the river continually moved closer and closer. British engineers tried different methods to stop the encroaching water but in the spring of 1772, a great freshet occurred in the Mississippi, which inundated the adjacent bottom and undermined one bastion and a part of the river wall of the fort. The commandant and garrison were ordered to raze and abandon the Fort and take up their quarters at Kaskaskia, which was thereafter the seat of British authority until the arrival of Colonel George Rogers Clark and his Virginia militia.

And so the once proud and impressive fortification, now abandoned and neglected slowly succumbed to the ravages of time and nature. Thankfully the mighty Mississippi changed course and moved slowly back to the West. Although it was only the forces of nature and geography that changed the course of the river and saved the site of the Fort the few habitants who chose to remain after the British arrived were recorded as saying they weren’t surprised the river had chased out the English but saved the old fort. They said “the Mississippi has always been a French river”. Perhaps they were right.

During its 300 years of existence Fort de Chartres has provided shelter for the soldiers stationed there and security for the civilians who had settled the area. It offered protection for the Native Americans who were already there and supplied a system of trade that afforded them the ability to acquire the things they wanted from the Europeans and a market for the products and services which the Europeans wanted from them. It protected a transportation system on the important waterways and overland routes so civilian and military traffic could move safely and efficiently keeping the communication and commerce channels open between the southern and northern areas of France’s empire in North America. Entrepreneurs and explorers used it as a stable base to go on to establish large agricultural, mining and merchandise trading communities into the new western frontier. Later as the whole area became more settled and a part of the newborn State of Illinois it’s abandoned ruins provided reusable building materials for the local residents and even the foundations for an immigrant German farm family to build on. It’s presence helped to make the American Bottom an agricultural supply house that sent and still sends food products not only to this country but all over the world.

Abandoned and almost buried in obscurity it still survived and by the efforts of people who understood the significance of this place it’s influence in the area can still be felt. Unburied, restored and revived today it provides a positive economic stimulus to the area as local people and visitors, some from very far away come to enjoy the beauty and history of this wonderful site. Not just a park to enjoy the outdoors for a family reunion or Saturday cookout with the usual ballgames and playground play it gives young and old alike a sense of history, a feeling that something important happened here.